Doing good science relies upon building your conclusions on solid, trustworthy observations and data. But what happens when you substitute your own critical thinking with blind faith in your calculator? This is the core of the “operator headspace” error concept. The situation that occurs when students trust the calculated result without performing a validity test, leading to a series of undetected errors.

One of my concerns is that allowing students to use calculators too early—or requiring expensive ones later—will cause their fundamental math skills to weaken. However, most experts agree that calculators are not the obstacle to learning math. The true hazard lies in misusing them in the educational setting.

The issue isn’t the number-crunching technology itself; it’s our failure to equip students with the essential “thinking skills” required to use it correctly. We must emphasize when to employ mental math to boost speed and cultivate number sense, and when to reach for a calculator for complex problems to save time.

A quick assessment of your mental safety net: If a calculation yielded a speed of for a jogger, would you catch the error? To build this internal defense mechanism, you must master the core principles: Dimensional Analysis, Scientific Notation, Estimation, and Significant Figures. These are more than just exam topics; they serve as your personal safeguards to ensure your answers are mathematically sound, logically consistent with the real world, and scientifically precise.

Skills First: You Master It Before You Automate It.

The absolute most important step is making sure you have a solid grasp of basic arithmetic, number sense, and estimation long before calculators become your go-to for everything. A student who understands why a calculation is happening won’t rely blindly on the machine.

The Calculator is a Helper, Not a Brain Replacement.

When you hit high school and college, advanced calculators become a must for dealing with complex equations and large amounts of data. At this point, the focus shifts to equipping yourself with the mental defenses you need to spot input errors and verify the machine’s answer. These are the higher-level skills that turn the calculator into a productivity boost instead of a crutch:

Unit Tracking (Dimensional Analysis): Making sure to follow the units throughout a problem to confirm the final unit makes sense. It’s a great way to catch a blunder.

Building a strong intuition for how big or small numbers really are: Scientific Notation.

Estimation: Performing a fast, mental estimate before punching in the numbers. If the calculator spits out something wildly different, you know to check your work immediately.

Precision Rules (Significant Figures): Learning when and how to report answers so you don’t claim more accuracy than the original measurements allow—it’s a sign of scientific maturity.

Breaking Down the Skills

I. Dimensional Analysis

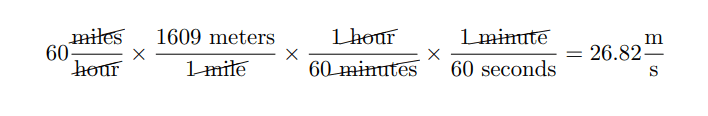

Dimensional Analysis is the key to error-free unit conversions. It operates on a simple principle: treat units like algebraic variables that must cancel out during multiplication or division. This is an immediate safeguard against the complex mistakes that arise when converting between different measurement systems (e.g., converting miles per hour to meters per second).

An incorrect final unit (e.g., calculating square feet when you need cubic feet for the volume of a dimensional object) is a certain sign that a conversion error occurred. It’s a proactive way to prevent errors and an effective tool for diagnosing exactly where a calculation went wrong.

The Golden Rule: Every conversion factor must equal 1. For example:

Example 1

Convert into

We start with the known value and multiply by a chain of conversion factors, ensuring units cancel diagonally:

The calculation then becomes:

II. Scientific Notation

Scientific Notation is the indispensable tool for understanding the magnitude of a number at a glance. By expressing a number as a coefficient multiplied by a power of ten (), it instantly reveals the number’s true magnitude—its actual size. The exponent () gives an immediate order-of-magnitude check, eliminating the complex demand for counting zeros.

This system protects against two common errors: mistyping the number of zeros (e.g., instead of ) and losing perspective on the number’s scale during long calculations. Seeing immediately communicates its small size, which is far clearer than counting a long string of leading zeros.

The calculator’s exponent function (or EE) is a safety mechanism against inputting long strings of zeros incorrectly. also streamlines the multiplication and division of huge and tiny numbers, making estimation easier.

Another bonus of using scientific notation, is that the value of is always <math data-latex="1\;\frac{<}{=}\;A

For Example:

Using the Law of Exponents, to divide two numbers in scientific notation form:

This type of manipulation of large and small numbers and the use of estimations will allow you to closely approximate the value to expect from your calculator. And, on multiple choice, timed exams (I.e. ACT, SAT), gives you an advantage, allowing you not to be dependent on using your calculator on these types of calculations at all.

III. Estimation

Estimation is arguably the most vital practice for combating “operator headspace errors,” and is the ultimate defense against absurd results. It involves performing a rapid, rough calculation—either mentally or on scratch paper—to determine the approximate range for the correct answer before running the precise, final calculation.

Estimation serves as a personal warning bell for:

Dumb Data Entry: It flags typos or misplaced decimal points that make the final answer ten, a hundred, or a thousand times too large or too small.

Crazy Results: If your calculation suggests a baseball is moving at , your estimate should instantly scream, “Impossible!” and prompt you to re-check your entire process.

IV. Significant Figures

Significant Figures are the foundation of scientific honesty in measuring the precision of a measurement. Every instrument has limits; a ruler marked only in millimeters cannot yield a micrometer measurement. Significant figures ensure that your calculated answer never claims a higher level of precision than the least precise measurement used in the initial data set.

Significant figure rules prevent the final answer from misleadingly implying high precision. If your calculator displays , but the least precise input you used had only , you must round the result to match that lowest value . This practice accurately communicates the reliability and uncertainty inherent in experimental data.

Summary

We’ve established that Estimation and Dimensional Analysis are the non-negotiable mental defenses you must learn to employ before committing to a calculation. These protocols are your barrier against operator headspace errors. However, the widespread introduction and mandatory use of powerful calculators—from simple four-function models in grade school to the advanced TI-series in college science and engineering—raises a critical and timely question:

“Does our reliance on these powerful tools effectively eliminate the very mental skills we’ve just deemed essential? ”

In my next post, I will address the concerns surrounding the appropriate use of calculators in the classroom to ensure the tool aids, rather than undermines, your scientific integrity.

Leave a comment