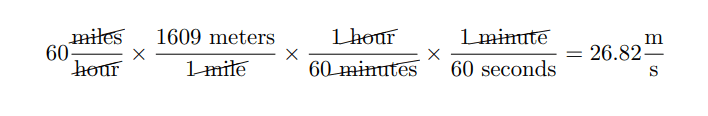

To follow up on my previous post, I cannot stress enough that four basic math skills: dimensional analysis, scientific notation, estimation, and significant figures – are prerequisites for anyone interested in math and sciences. Mastering these concepts helps stop the “operator headspace” mistakes that happen when you use your calculator as a crutch.

My biggest concern is that leaning too much on calculators is actually making students worse at fundamental math. For example, in the students I tutor, I’m seeing a drop in their ability to do mental math, a poor sense of estimation, and a failure to build that crucial “number sense” – that gut feeling about how numbers work and whether an answer makes any sense.

It’s a bit disappointing to me when I can perform math functions such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and PEMDAS calculations faster and more accurately in my head than my students can on their fancy $100 calculator.

Therefore, the question I’m asking is:

“When kids let the calculator do the work, do they skip the mental practice needed to really lock in these vital skills?”

What Do the Experts Say?

Educational research points to a broader consensus: the impact of calculators isn’t automatically negative. The general feeling among experts is that when calculators are used correctly, they don’t inherently make students less capable at math. Instead, they suggest that any negative results usually come not from the calculator itself, but from using it poorly or too much. This often boils down to schools failing to have an intelligent, deliberate plan for when and how to bring this technology into the classroom. When the calculator becomes a crutch – used for problems students could easily do in their heads or on paper – that feared skill loss can definitely happen. But on the flip side, when they’re introduced as tools for digging into tougher concepts, checking answers, or handling the annoying arithmetic in advanced problem-solving, they can be helpful. They let students focus on deeper mathematical thinking and understanding.

How Should We Address These Concerns?

Math educators strongly advocate a structured, phased approach to the introduction of calculators:

- Prioritize Traditional Methods: Students must first be required to build a strong foundation in mathematics through traditional mental math and written arithmetic methods. This guarantees that these techniques and number sense are firmly established.

- Introduce Calculators as a Tool, Not a Replacement: Calculators should be introduced later in the elementary school years (not second grade), transitioning from an everyday practice to a valuable educational tool. Their primary function should be to support the student, not replace mental calculations.

- Introduce Calculators as a Resource for Checking Answers: Confirming answers acquired through mental or written technique.

- Introduce Calculators for Exploring Complex Numerical Systems: In secondary and post-secondary classrooms, calculators are introduced as a tool for investigating sequences or statistics on large data sets where calculation time is prohibitive.

- Introduce Calculators for Solving Conceptually Challenging Problems: Working with complex problems where the challenge lies in understanding the concept and setup, not in the basic arithmetic calculation itself.

This is an intelligent approach to introducing the calculator in the classroom, as it allows students to actively check their work. This is all about helping them master the calculations and truly understand how the math works. The goal here is to boost their learning, not get in the way of it.

High School and College STEM Courses: The Dangers of Calculator Over-Dependence

When you get to advanced math and science courses, relying too much on a calculator isn’t just about whether you can do the basic arithmetic (you should be able to); it’s about some more concerning issues. Specifically, whether using the calculator too often can affect your grasp of the concepts, make you rusty at solving problems algebraically, and weaken your crucial ability to estimate answers quickly to check your work.

Using powerful tools like TI graphing calculators can be a risk for learning. Certainly, these instruments make complex math operations simple, but that convenience can slow down a student’s development. Students who always simply punch numbers into their calculator to get an answer often miss out on building important “number sense.” This basic skill is key to quickly seeing if an answer is logical. Without it, students are more likely to accept completely wrong answers due to simple input errors because they haven’t developed the gut feeling that an answer is just plain wrong. Getting that immediate result skips the necessary learning steps of estimating and checking the math in your head.

Graphing calculators, while excellent tools that may assist a student’s understanding of the relationship between an algebraic equation and its graph, may also lead to over-reliance. When students rely too heavily on the calculator, they may be satisfied with merely seeing relationships – such as the curve’s shape or the location of an equation’s roots – without making the effort to understand the fundamental mathematical reasoning.

True mathematical mastery requires knowing not only what the graph looks like, but why it is structured that way. This deeper knowledge develops through hands-on engagement, not just by pressing buttons. The danger is that the calculator becomes a black box: it provides correct answers without explaining the logic behind the calculations, ultimately blocking the development of real mathematical understanding.

I must admit I am not a fan of the Ti-83/84 series of graphing calculators, perhaps because I have not used them as much as the students I‘ve tutored. I use the Ti-30 series for calculations, and for graphing functions, I use Desmos (www.Desmos.com), which I find to be a powerful tool that produces graphs I can easily manipulate and that are easier to see on my computer screen. I recommend it to every student I work with.

I believe it is crucial to learn how to evaluate a graph, a skill that goes beyond just plugging an equation into your graphing calculator and seeing the resulting graph on the screen. I had a Physics professor at Centre College, Dr. Marshall Wilt, who insisted that we learn how to graph and interpret the experimental data we obtained in the laboratory, as well as the relationships between small changes in inputs and the resulting output for equations such as the distance equation: ( ). Albeit this was in the late 1970s, before graphing calculators were available, this was a skill that I used throughout my career.

Learning to evaluate graphs, regardless of how they are produced, and understanding the data they represent is a critical skill, useful, for example, on the ACT Science section, where graphical interpretation determines the correct answer.

Also, understanding graphical components such as slope and y-intercept is important for data interpretation, especially in chemistry, where they represent the reaction rate and the endpoints of a reaction.

From a Positive Perspective: How Calculators Help

Calculators are beneficial because they automate the long, repetitive mathematical calculations. This automation means you don’t have to waste time doing tedious work manually; for example, long division problems, complex multiplications, or solving big sets of equations.

The payoff? Students can focus their attention on bigger concepts. Instead of endless drills, the focus shifts to building higher-order thinking skills, figuring out the best way to tackle a problem, and really getting the math – like understanding of why a procedure works and when to use it. Basically, students can put their energy into setting up the problem, interpreting what the answer means, and grasping the core math ideas rather than getting bogged down in the steps of calculation itself.

Graphing calculators are great tools for exploring, questioning, and visualizing math concepts, turning complex equations into graphs. Students can quickly try out ideas and immediately see what happens when they tweak a function—like instantly watching how changing the numbers in a quadratic function () shifts the parabola’s shape, direction, and peak. This fast, back-and-forth feedback encourages students to ask “what if?”, sparks their curiosity, and helps them really see the connection between the formula and the graph.

Calculators promote real-world data analysis skills. Restricting math problems to simple, whole numbers creates an artificial learning environment that fails to prepare students for the “messy” data they will encounter in professional fields such as science, finance, and engineering. Real-world applications invariably involve complex and irregular numbers. By using calculators, students can engage with authentic, complex data sets. This practice not only allows them to tackle applicable, practical problems that mirror professional scenarios but also reinforces the practical application of mathematics, thereby significantly boosting their skills in data interpretation and analysis.

Summary

The answer to my initial question:

“When kids let the calculator do the work, do they skip the mental practice needed to really lock in these vital skills?”

is complex. The expert consensus suggests the answer is no, not necessarily. The problem isn’t the calculator itself, but how it is used.

When a calculator is used too soon, as a replacement for mental math and estimation, it becomes a crutch for problems a student should solve independently. It clearly sidesteps the mental exercise required to master fundamental skills such as dimensional analysis, estimation, and significant figures.

The path forward is clear: a structured, phased approach to integrate this technology is essential.

- Foundation First: Students must first master fundamental arithmetic and algebraic manipulation using traditional methods. This ensures the critical development of number sense and the ability to estimate and check answers quickly.

- Calculators as Investigational Tools: Once the foundation is solid, the calculator changes from a potential crutch into a powerful tool for learning. It allows students to automate tedious calculations in advanced problems, freeing them to focus on setting up the problem, understanding the concept, how changes in variables affect the algebra, and interpreting results.

- Understanding the “Why”: For advanced topics, particularly in STEM, the goal is not just the correct answer, but mastering the math itself – understanding why the graph looks a certain way or why a procedure works. The graphing calculator can illustrate the relationship between algebraic equations and their graphs (), but it must be paired with a conceptual understanding beyond merely pressing buttons.

The goal is to develop mathematically proficient students capable of determining when to rely on mental calculation, when to use written methods, and when to employ a powerful device like a calculator. While the calculator is an essential instrument for today’s STEM students, it must serve as a secondary aid to mathematical reasoning, not a substitute for it.