If you are an aspiring STEM student, or the parent of one, I want you to consider a terrifying possibility: It is possible to have a 4.0 GPA and know/retain almost nothing.

I saw this contradiction in the students I would tutor. They were bright, hardworking, and ambitious. They had mastered the art of getting the “A.” They knew how to take tests, follow instructions, and allocate their time to receive a high score.

However, if I asked them to apply a physics concept from two weeks before to a new problem assigned that day, they would freeze. Their knowledge of the material (data) was gone.

This is the Grade Illusion. We have built an educational culture – especially in high-stakes fields like STEM, where the “High Score” has become the product. But in the real world, the test scores from high school and college courses are irrelevant. The only thing that matters is mastering the content.

If you want to survive the transition from “A-student” to “successful scientist,” you need to understand how your own mind works. You need to stop renting knowledge and start owning it.

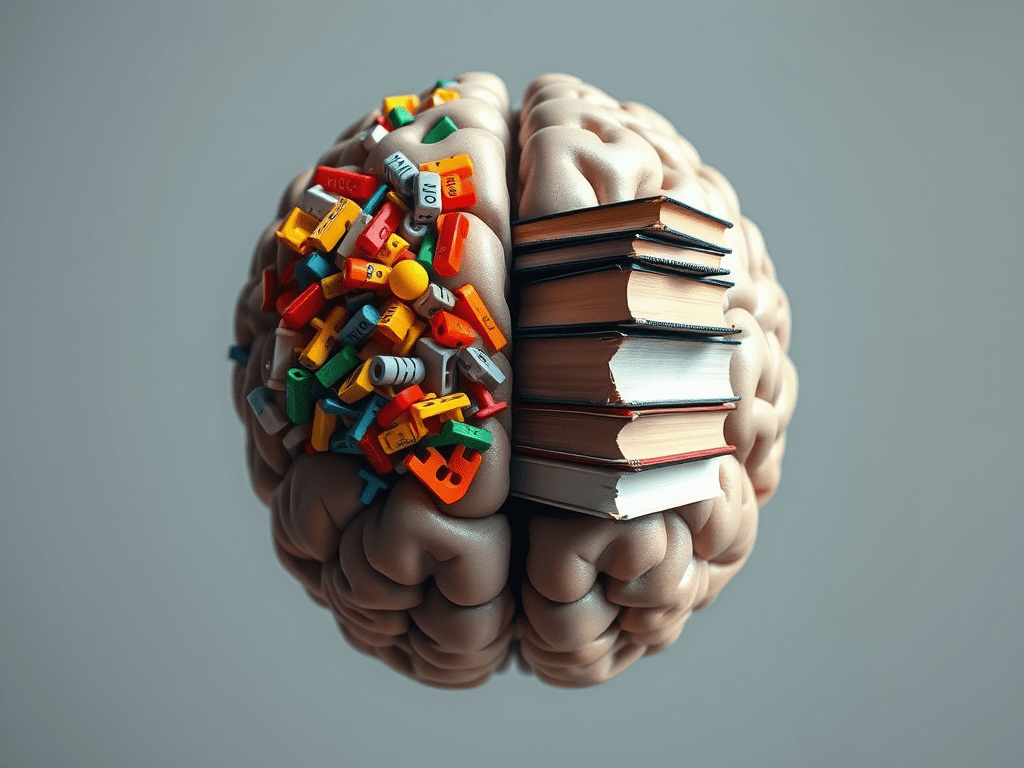

The Knowledge Retention Misconception: RAM vs. Hard Drive

To understand why intelligent students often feel like impostors, we need to examine how the brain stores information.

Think of your brain like a computer. You have two types of storage:

- RAM (Random Access Memory): This is short-term, high-speed memory storage. It holds the data you need right now. It is volatile; when the power cuts (or the test ends), the data is wiped to make room for the next task.

- The Hard Drive: This is long-term storage. It is slower to write to, but the data remains there forever, ready to be recalled years later.

The modern educational system encourages you to use your RAM, not your Hard Drive. We call this Cramming, or as we discussed in an earlier blog post, the act of memorization/regurgitation.

When you cram for a calculus midterm, you are loading complex formulas into your RAM. You hold them there—stressfully—for 24 hours. You walk into the exam, dump the RAM onto the paper, and get a 95%. You feel successful.

But 48 hours later, that RAM is cleared to make space for Chemistry. The “Save to Hard Drive” function never happened.

The Science of Forgetting

This isn’t just a metaphor; it is a biological fact. In the late 19th century, psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus mapped the “Forgetting Curve.”

The curve shows that without deep processing (the struggle necessary to understand something), humans lose roughly 50% of new information within a day and 90% within a week.

The student who crams and gets an “A” peaks at 100% on Tuesday morning. By next Tuesday, their retention dropped to nearly the same level as that of the student who failed. The grade is a record of what you knew for one hour, not what you carry into your career.

From an economics perspective, consider this as the difference between Renting and Owning.

- Cramming is Renting. You pay a high price in stress and sleep deprivation. You get to “live” in the knowledge for a day. But once the test is over, your “lease” is up, and you are evicted. You have zero equity.

- Deep Learning is Owning. You pay a “mortgage” of daily, consistent study. It feels slower. It feels harder. But two years later, when you are designing a load-bearing bridge, for example, that physics principle is yours.

The Illusion of Competence

“But I got an A!” you might argue. “The test says I know the material.”

Does it?

In 1956, in the publication “Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals,” a committee of educators chaired by Benjamen Bloom developed a framework to rank levels of understanding called “Bloom’s Taxonomy.”

Shutterstock

Most high school tests—and frankly, many college exams—operate at the bottom three levels: Knowledge (learn the formula), Comprehension (understand when to use the formula), and Application (plug numbers into the formula).

If you are good at memorization, you can ace these tests without ever moving up the pyramid. But a career in STEM fields lives entirely at the top three levels:

- Analysis: Why did the experiment fail?

- Evaluation: Which method is best for this specific application?

- Synthesize (Create): Develop an improved solution that isn’t in the textbook.

The Illusion of Competence

This creates the Illusion of Competence. You have a transcript full of “A’s” that certify you are an expert, but your internal drive has never been stress-tested at the “Analysis” or “Synthesis” level. When you eventually hit a problem that requires those skills, you don’t just struggle—you crash.

The most dangerous side effect of the Grade Illusion isn’t academic; it’s psychological.

The Performance = Identity Misconception

When you spend your entire life chasing the “High Score,” you begin to associate your Performance with your Identity. You believe the equation: My Grade = My Worth.

In STEM, this is lethal. In English class, a grade of “C” might seem subjective. In Physics or Chemistry, a “wrong answer” is objectively wrong. If you tie your self-worth to getting the right answer, every mistake feels like a character flaw.

You need to adopt the mindset of a Scientist:

- You are the Learning Process itself. You are the curiosity, the work ethic, the resilience.

- The Grade is just Data. It is simply the output of a single, specific experiment on a single specific day.

For example, if a Ferrari engine performs poorly because it had bad fuel, we don’t say the engine is trash. We say the input (fuel) was wrong. Similarly, if you fail a test, it doesn’t mean you are broken. It means your variables—your study habits, your sleep, your preparation—were off.

A bad grade is not your identity. It is guidance.

Breaking the Cycle

Ready to shift from being a “Grade Hunter” to a true “Learner”? Use these two simple techniques to pinpoint where you are in that transition and determine the necessary steps to move forward.

1. The “Two-Week Audit.”

I challenge you to a challenging experiment. Take a test you aced two weeks ago. Sit down and take it right now, without reviewing your notes.

The difference between your score then (95%) and your score now (55%) is your Fake (Lost) Knowledge. That 40-point gap represents wasted energy. It is time spent renting, not owning. If the gap is huge, your study method is broken, regardless of your GPA.

2. The Feynman Technique (The Ownership Test)

Physicist Richard Feynman had a simple rule for understanding, which he borrowed from Albert Einstein. To prove you have mastered a concept, you must be able to explain it in simple language, without jargon, to someone who has no background in the topic (like a smart 12-year-old).

If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it. You have only memorized the definition. You are stuck at the bottom of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

The Bottom Line

The world is full of influencers and algorithms showing you the easy way to obtain a high test score on the ACT and achieve the most sought-after degrees, jobs, and accolades. Yet they rarely show you how to retain the knowledge required for long-term success.

Success in STEM requires three “old school” prerequisites that cannot be skipped: Curiosity, a Passion for Learning, and a Passion for Solving Problems.

If you have these, the grades will eventually follow. But more importantly, later in life, when the grades stop mattering, the expertise will remain.