You may be doing well in your math and science courses, or perhaps you’re already interested in areas such as computer programming, robotics, or video game design. While a passion for STEM and strong academic performance are certainly vital, true success in these fields requires more than just intelligence.

The key drivers—the qualities that will propel you through challenging projects, demanding courses, and even career setbacks—are the four absolutely vital tools in your personal growth toolkit for anyone charting a course in STEM: Initiative, Resolve, Perseverance, and Resilience.

What is Initiative, Resolve, Perseverance, and Resilience?

1. Initiative

What it is: The ability to self-start, take action without being told, and seek out new opportunities or skills.

Why it matters in STEM: The STEM fields are constantly evolving. What you learn today may be outdated in five years. Initiative is crucial for lifelong learning—the willingness to constantly teach yourself new skills (computer programming, robotics, advanced data analysis, or new analytical instrumentation) to remain current and competitive in the industry.

When performing research or problem-solving, it takes initiative to troubleshoot errors, design a better experiment, or learn to use a new piece of equipment before it’s required. It’s what drives you to excel.

Example: Your Chemistry professor assigns an open-ended laboratory project. The explicit expectation is a successful, unique final product. You must show the initiative to search for resources, organize the necessary equipment and reagents, and learn to operate the necessary tools needed to complete the project because the assignment demands it, not just because you feel like it.

2. Resolve

What it is: A firm determination to achieve a specific goal, resisting distractions, and maintaining focus even when things get tough. The unwavering focus needed to complete a difficult project, solve a complex equation, or commit to the years of study required for a specialized field of study.

Why it matters in STEM: STEM fields demand long-term commitment. Resolve is what helps you stay committed to completing that difficult assignment, even when exhaustion hits. Push through a difficult physics derivation, knowing the understanding will unlock new perspectives. See past a frustrating semester or a challenging first-year chemistry, physics, or math course, reminding you of your ultimate career aspirations. It’s the inner conviction that keeps you on track.

Example: Introductory college courses, such as Organic Chemistry, Physics, and Calculus, are often intentionally challenging to test your preparedness to succeed in upper level courses. When faced with a low grade, resolve is the quality that prevents you from abandoning your major. Initiative is the drive to seek out help by finding a tutor, joining a study group, or meeting with the professor to grasp the material you do not understand, instead of simply giving up.

3. Perseverance

What it is: The sustained effort to keep working despite difficulties, serving as the dedication required to solve tough problems through hours of calculations, research, or repeated experiments. It’s the long-term, consistent effort.

Why it matters in STEM: STEM is rarely a straight line to success. Perseverance means spending countless hours debugging computer programming, even when you’re convinced it’s flawless. Re-running an experiment five times because you’re confident there’s a pattern you’re missing. Staying up late to understand a complex mathematical concept until it finally clicks.

Example: You struggle with a Chemistry laboratory assignment and are tempted to give up. Your instructor intervenes, not by giving you the answer, but by offering a small suggestion, confirming the difficulty of the task, and requiring you to follow up in an hour. This structured support prevents you from feeling abandoned in your efforts, reinforces the importance of struggle, and teaches you the value of perseverance.

While the ultimate decision to continue is yours, external factors, the support from your instructor, are essential. The setting of an expectation, the modelling of how to continue in the process, and the structured support act as powerful motivations, transforming your ability to just keep going into an established, automatic behavior (perseverance).

4. Resilience

What it is: The capacity to recover quickly from setbacks, disappointments, or outright failures, viewing setbacks not as defining moments but as valuable data and learning opportunities.

Why it matters in STEM: Failure isn’t a setback in STEM; it’s a feature. Scientific discovery often involves many “failed” experiments before a breakthrough. Resilience allows you to: bounce back from a low test score, analyze what went wrong, and adjust your study habits.

Example: It can be challenging for you to picture what “resilience” looks like. Mentors provide a crucial model. When you witness your research advisor’s experiment fail, and instead of getting discouraged, your advisor calmly analyzes the data, identifies the potential sources of error, and immediately starts correcting the issues for the next trial run. These actions model resilience and teaches you how to respond appropriately to setbacks.

STEM fields are characterized by constant challenges and an emphasis on complex problem-solving. Success relies less on your natural talent and more on your willingness to engage in a productive learning process. And that success rarely comes on the first try. It is common for an experiment to produce unexpected results or a mathematical proof to contain an error. Instead of seeing these setbacks as personal shortcomings, students need the mindsets of resilience and perseverance to see a failure as a starting point.

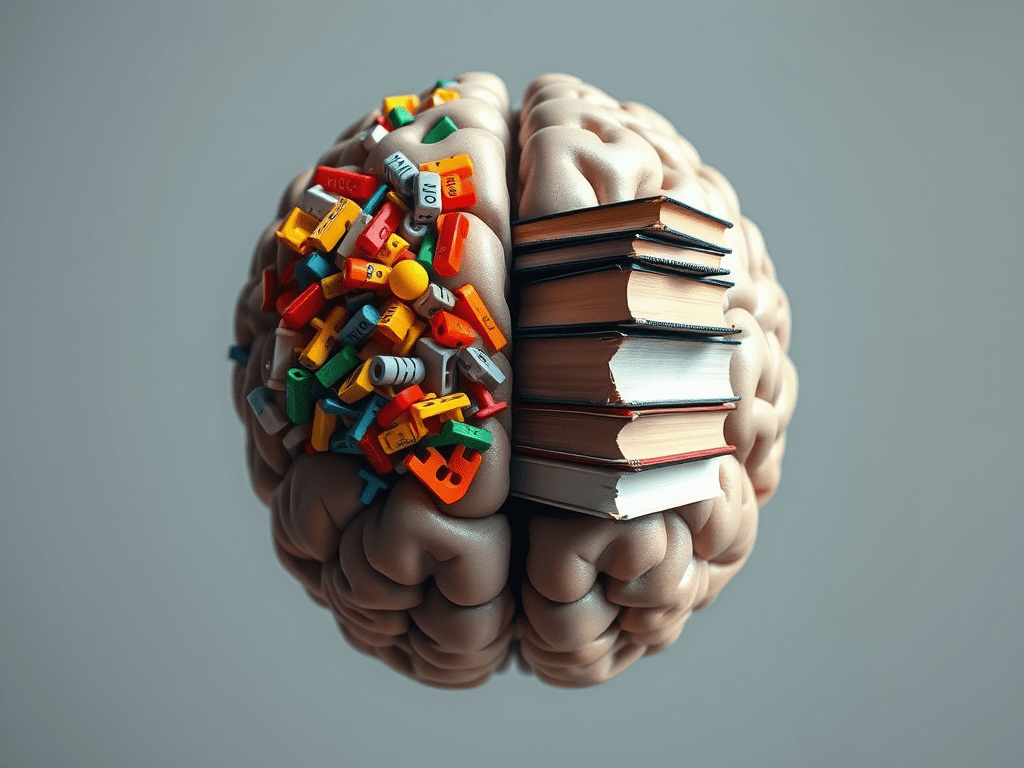

Is Initiative, Resolve, Perseverance, and Resilience a Personality Trait or a Learned Skill?

Initiative, resolve, perseverance, and resilience are generally understood as learned behaviors. Psychologists like Carol Dweck argue that these qualities stem from a Growth Mindset—the belief that our abilities and intelligence can be developed, rather than a fixed personality trait. While some people might appear naturally more determined to manage and learn from their struggles, everyone has the capacity to develop these essential skills.

Think of initiative, resolve, perseverance, and resilience as learned skills that, when practiced consistently, become an integral, defining part of your character or personality. For a STEM student, it is critical to recognize the value in treating them as skills that require deliberate practice.

The Power of Role Models, Mentors, and External Expectations

The skills of initiative, resolve, perseverance, and resilience isn’t something you can achieve entirely on your own, however you can always begin the process. The most effective and the smoothest path to growth in these areas requires external guidance. Role models, mentors, and the right external expectations act as a vital catalyst in forging these qualities.

How do role models, mentors, and external expectations cultivate these critical skills? Here are four key examples:

Observation: Professors, Mentors, and Role Models provide critical “how-to” knowledge. Observing an experienced chemist handle an instrument failure calmly or a scientist gracefully accept and learn from a failed experiment offers a real-world demonstration of resilience and perseverance in action.

Accountability: External expectations, whether it is from a professor, mentor, or a course syllabus, establish defined goals and deadlines that require action. Taking on a challenging project with its external pressures, its deadlines and reporting requirements, serves as a catalyst. It triggers the initiative needed to start and, crucially, builds the internal resolve and strength required for sustained effort toward completion.

A Defined Strategy for Success: Effective teachers and mentors avoid simply giving answers. Instead, they offer focused, constructive feedback, guide individuals through roadblocks, and recognize small achievements. This strategic support reinforces successful behaviors, driving long-term competence and success.

Reinforcement and Feedback: These critical skills are only learned effectively when you receive balanced feedback from your professors and mentors, parents as well – positive reinforcement when you suceed and constructive criticism when you fall short.

A Strategy for Your Personal Growth and Success

As you navigate your academic life and plan for a career in science, technology, engineering, or math, your focus must extend beyond formulas and facts. You need to actively look for opportunities to develop your initiative, resolve, perseverance, and resilience. So take action with the following approach:

1. Embrace the Hard Stuff: Never shy away from difficult assignments or complex projects. Challenges are opportunities in disguise.

2. Treat Failures as Data: Every setback is not an end, but a valuable data point. Analyze what went wrong and adjust your approach.

3. Actively Seek Mentors: Find someone whose approach to challenges inspires you, and commit to learning from their wisdom and experience.

4. Practice Self-Reflection: When things get tough, take a moment to ask yourself: How did I react? What could I do differently next time?

Conclusion

These qualities are not just career buzzwords; they are the foundation of personal growth and the essential fuel for scientific discovery and innovation. The combination of strong grades and these four psychological attributes is what ultimately separates a good student from future success in their career path, capable of making a difference in a STEM field. Cultivate them, and you will do more than just succeed in STEM; you will thrive in every aspect of your life.